Library Self-aware universe. How consciousness creates the material world. Chapter 10: Exploring the Mind-Body Problem

PART III. SELF-REFERENCE: HOW ONE BECOMES MANY

Centuries ago, Descartes portrayed the mind and body as separate realities. This dualistic gap still permeates our understanding of ourselves. In this part we will show that monism, based on the primacy of matter, is not capable of expelling the demon of dualism. Only idealistic science—the application of quantum physics interpreted according to the philosophy of monistic idealism—really bridges the gap.

We will see that idealistic science not only heals the broken mind-body relationship, but also answers some of the questions that have puzzled idealistic philosophers for centuries—for example, how does one consciousness become many? Or, how does the world of subjects and objects arise from integral being? The answers to such questions are contained in concepts such as complex hierarchy and self-reference – the ability of a system to see itself as separate from the world.

In India there is a wonderful legend about the origin of the Ganga River. In reality, the Ganga is born from a glacier high in the Himalayas, but legend says that the river begins in the heavens and flows down to earth through Shiva’s braided hair. The Indian scientist Jagadish Bose, who expressed far-reaching ideas regarding plant consciousness, wrote in his memoirs that as a child, listening to the sounds of the Ganges, he wondered about the meaning of the legend. As an adult, he found the answer – cyclicality. The water evaporates to form clouds, then returns to the earth as snow, lying on the highest peaks of the mountains. The snow melts and becomes the source of rivers, which then flow into the ocean to evaporate again, continuing the cycle.

In my youth, I too spent hours on the banks of the Ganges, pondering the meaning of the legend. For some reason, it seemed to me that Vose had not found a definitive answer. Cyclicity, of course, but what is the meaning of Shiva’s braided braid? I didn’t know the answer then.

I had seen many different rivers, but the legend continued to puzzle me until I read Douglas Hofstadter’s book Gödel, Escher, Bach: The Eternal Golden Braid. In legend, the river Ganga (another name for the divine mother) symbolizes the formless principle behind the manifested form – Plato’s archetypes; and Shiva is the formless principle behind the manifested self-consciousness – the unconscious. Shiva’s braided braid represents a complex hierarchy (Hofstadter’s eternal golden braid). Reality comes to us in manifest form through a complex hierarchy just as Ganga descends into the world of form through Shiva’s braided hair.

We will find that this answer leads to the idea of a spectrum of self-awareness. We will see that beyond the ego there is a self. Taking this larger self into account allows us to connect the various personality theories of modern psychology—behaviorism, psychoanalysis, and transpersonal psychologies—with the concepts of self expressed in the great religious traditions of the world.

CHAPTER 10. EXPLORING THE MIND-BODY PROBLEM

Before exploring how idealistic philosophy and quantum theory can be applied to the mind-body problem, let us briefly review contemporary mainstream philosophy. We all have an overwhelming intuitive feeling that our mind exists separately from our body. There is also the opposite feeling (for example, when we experience bodily pain) that the mind and body are one and the same. In addition, we intuit that we have a self separate from the world – an individual self that is aware of everything that happens in our mind and our body, and by its own (free?) will causes some of the actions of the body. Philosophers of the mind-body problem explore these intuitions.

First, there are philosophers who argue that our intuitions about a separate mind (and consciousness) from the body are correct; these are dualists. Others deny dualism; these are monists. One school, material monism, believes that the body is primary and that mind and consciousness are merely epiphenomena of the body. The second school, monistic idealism, proceeds from the primacy of consciousness, considering the mind and body as epiphenomena of consciousness. In Western culture, especially in recent times, material monism has dominated monistic philosophy. On the other hand, in the East, monistic idealism retained its position.

There are many approaches to the mind-body problem, many ways of drawing conclusions, and many subtleties that require explanation. I would like you to keep these subtleties in mind as you join me on a tour of what I will call the University of Mind-Body Studies. Imagine all the great thinkers who have studied the mind-body problem gathered here, teaching in a traditional department the solutions to this problem that have been proposed throughout history – old and new, dualistic and monistic. Before you enter the university, I warn you: remain skeptical, and before agreeing to any philosophy, relate it to your own experience.

You easily find the university – a seductive smell spreads around it. As you get closer, you see that the scent is coming from a fountain called Meaning, located at the entrance. The elixir flowing from this fountain is always changing, but its aroma is always captivating.

You walk through the gate and look around. The university buildings belong to two different styles. On one side of the street there is an old, very elegant building. You have a weakness for classical architecture, so you turn in that direction. The modern skyscraper on the other side can wait.

However, as you approach the building, a picketer stops you and gives you a leaflet that says:

Beware of dualism!

Dualists take advantage of your naivety by preaching outdated ideas. Consider this: Suppose one of the robots in a Japanese car factory is conscious, and you ask its opinion about the mind-body problem. According to our leader, Marvin Minsky: “When we ask this kind of creature what kind of creature it is, it simply cannot answer directly; it must study its patterns. And it must answer by saying that it appears to be dual—consisting of two parts, “mind” and “body.” Robot thinking is primitive thinking. Don’t give in to it. Insist on monism that offers modern, scientific and sophisticated solutions.

“But,” you object to the picketer, “I myself sometimes feel this way—like separate mind and body. You don’t say… But in any case, who asked you! And just so you know, I like the old wisdom. I want to check everything myself, so please let me pass.”

Shrugging his shoulders, the picketer makes way for you. There is a sign in front of the building that reads: College of Dualism, Dean Rene Descartes. The very first room you enter, you are overcome with nostalgia. A middle-aged man, who you assume is a professor, silently stares at the ceiling. His face is somehow familiar to you, and you feel like you should recognize him. Suddenly you notice an emblem on his desk:

Cogito, ergo sum. Well, of course! This must be Rene Descartes.

Descartes responds to your greeting with a kind smile. With shining eyes, he proudly answers your request to explain the relationship between mind and body. He gives a clear explanation of his principle of “I think, therefore I am”: “I can doubt everything, even my own body, but I cannot doubt that I think. I cannot doubt the existence of my thinking mind, but I can doubt the existence of my body. Obviously, the mind and the body must be different things.” He says that there are two independent substances – soul substance and physical substance. The substance of the soul is indivisible. The mind and soul are made of this substance – an indivisible, irreducible part of reality, responsible for our free will. On the other hand, physical substance is infinitely divisible, reducible, and governed by scientific laws. But the substance of the soul is controlled only by faith.

“Free will is self-evident,” he says in response to your question, “and only our minds can know it.”

“Because our mind does not depend on the body?” – you ask.

“Yes”.

But you are not satisfied. You remember that the Cartesian dualism of mind and body violates the laws of conservation of energy and momentum, established beyond any doubt by physics. How could the mind interact with the world without periodic exchanges of energy and momentum? But we always find that the energy and momentum of objects in the physical world are conserved, remain the same. As soon as the opportunity arises, you mutter an apology and leave Descartes’ office.

On the door of the next office there is a name written: Gottfried Leibniz. As you enter, Professor Leibniz politely asks: “What were you doing there with old Descartes? Everyone knows that Descartes’ good interactionism does not stand up to criticism. How can the immaterial soul be materially located in the pineal gland?

– Do you have a better explanation?

– Of course. We call it psychophysical parallelism.

He explains succinctly: “Mental events occur independently of, but parallel to, physiological events in the brain. No interaction, no embarrassing questions.” He smiles smugly.

But you are disappointed. Philosophy does not explain your intuitive feeling that you have free will, that your self has causal power over the body. It sounds suspiciously like sweeping dirt under the rug—out of sight, out of mind. Smiling to yourself at your own pun, you notice that someone is waving their hand at you invitingly.

“I am Professor John K. Monist. All this dualistic talk about the mind must be making you dizzy,” this man says.

You confess your growing mental fatigue, and he declares with a hint of sarcasm, “The mind is a ghost in the machine.” In response to your obvious confusion, he continues: “A visitor came to Oxford, who was shown all the colleges, buildings, etc. Subsequently he asked – where is the university? He didn’t understand that colleges are universities. The university is a ghost.”

“I think the mind must be more than a ghost. After all, I have self-awareness…”

The man interrupts you irritably: “It’s all an illusion; the problem is using the wrong language. Go to the monists on the other side; they will tell you.”

Perhaps the man is right; after all, monists can be experts in truth. There are undoubtedly many more offices in the huge shiny building on the other side.

But here you are also greeted by a picketer. “Before you go in there,” he asks, “I just want you to know that they will try to deceive you with promises of materialism; they will insist that you must believe their statements because evidence will “certainly” be forthcoming in the near future.” You promise to be careful and he backs off. “I’ll pray for you,” he says, crossing his fingers.

The lobby looks luxurious, but you hear the noise, which comes mainly from the auditorium, on the door of which there is a notice on the door with the topic of the lecture: “Radical Behaviorism.” Inside the auditorium, a man is pacing back and forth, speaking to a fairly small audience. As you get closer, you realize that the lecturer is talking about the work of the famous behaviorist B.F. Skinner. Well, of course! A sign in front of the college states that its dean is Skinner; It is natural that his work should have a special position here.

“According to Skinner, the problem of mentalism can be avoided by going directly to prior physical causes, leaving aside intermediate feelings or states of mind,” says the lecturer. “Only those facts that can be objectively observed in human behavior in relation to the previous history of his environment should be considered.”

“Skinner wants to free himself from the mind – no mind, no mind-body problem – just as the parallelists try to eliminate the problem of interaction. In my opinion, both he and they avoid the problem to a greater extent than solve it,” you say to the professor in the next office.

“It is true that radical behaviorism is too narrow. We must study the mind, but only as an epiphenomenon of the body. Epiphenomenalism, the professor explains, is the idea—and, by the way, the only idea that makes sense in the mind-body problem—that mind and consciousness are epiphenomena of the body, produced by the brain, just as the liver produces bile. Tell me, how could it be otherwise?

“You should tell me this – you are a philosopher. Explain how the epiphenomenon of self-awareness arises from the brain?”

“We haven’t figured it out yet. But we will certainly find out. It’s only a matter of time,” he insists, wagging his index finger.

“Promises of materialism, just as the picketer warned!” – you mutter to yourself as you walk away.

In the office opposite the lecture hall, Professor Identity is persistently courting you. He doesn’t want you to leave his department without knowing the truth. In his opinion, the truth lies in the identity of the mind and the brain. They are two aspects of the same thing.

“But this does not explain my experience of the mind; if that’s all you have to say, then I’m not interested,” you state as you head towards the door.

But Professor Identity wants you to understand his position. He says that you must learn to replace mental terms in your language with neurophysiological terms, because for every mental state there is ultimately a corresponding physiological state that is actually real.

“Some people still preach something like this called parallelism.” You experience genuine pleasure because you can now easily understand philosophical terms.

In response, the professor, with professional confidence, offers another interpretation of the identity theory: “Even though the mental and the physical are the same thing, we distinguish them because they represent different ways of knowing. You have to study the logic of categories before you fully understand this, but…”

This last statement finally pisses you off, and you irritably say to him: “Listen, I have been walking from one office to another for several hours with a simple question: what is the nature of our mind that gives it free will and consciousness? And all I hear in response is that I can’t have such a mind.”

The professor is not embarrassed. He mutters something about consciousness being a vague and confusing concept.

You are still angry: “Consciousness is unclear, right? So, are you and I unclear? Then why do you take yourself so seriously?

You quickly leave before the puzzled professor can answer you. Along the way you reflect – perhaps my action was a conditioned reflex, initiated in my brain, and simultaneously arising in my mind as what seemed to be free will. Can philosophy really prove that man has free will, or is it powerless? But philosophy can wait—all you care about right now is a portion of pizza and a glass of beer.

Your attention is distracted by a dimly lit part of the building. Upon closer inspection you discover that the architecture here is older. The new building was built on parts of the old one. A sign catches your eye: “Idealism. Enter at your own risk. You may never be a true mind-body philosopher again.” But the warning only increases your curiosity.

The first office belongs to Professor George Berkeley. Interesting man, this Berkeley. He says, “Look, whatever you say about physical things ultimately refers to mental phenomena—perceptions or sensations, doesn’t it?”

“It’s true,” you reply, impressed by his words.

“Imagine suddenly waking up and discovering that you were dreaming. How can you distinguish material substance from dream substance?”

“I probably can’t do that,” you admit. “But there is a continuity of experience.”

“Continuity be damned. Ultimately, all you can trust, all you can be sure of, is the stuff of the mind: thoughts, feelings, memories and all that. So they have to be real.”

You like Berkeley’s philosophy; it makes your free will real. However, you hesitate to call the physical world a dream. Besides, there’s something else that’s bothering you.

“It seems to me that your philosophy has no place for those objects that are not in anyone’s mind,” you complain.

But Berkeley replies smugly: “They are in the mind of God.”

And this sounds like dualism to you.

A darkened room catches your interest and you look into it. Well well! What is this? There is a shadow theater going on on the wall, projected by the light behind, but the people watching the action are tied to their seats and cannot turn around. “What’s happening?” — you ask the woman with the projector in a whisper. “Oh, this is a demonstration of Professor Plato’s monistic idealism. People see only the shadow theater of matter and are seduced by it. If only they knew that the shadows are cast by the “more real” archetypal objects behind them – the ideas of consciousness! If only they had the fortitude to explore the light of consciousness—the only reality,” she laments.

“But what keeps people glued to their seats—I mean, in real life?” – you are interested.

“Why do people like illusion more than reality? I don’t know how to answer this. I know that in our faculty there are people – I think they are called Eastern mystics – who say that everything is caused by Maya, or illusion. But I don’t know how Maya works. Perhaps if you wait for the professor…”

But you don’t want to wait. Outside, the corridor becomes even darker, and on the wall an arrow with the inscription “Toward Eastern Mysticism” is barely visible. You are curious but tired; you want beer and pizza. Maybe later. Undoubtedly, the Eastern mystics will agree to wait. Easterners are known for their patience.

But you have to wait for beer and pizza. As you leave the building, you find yourself in the middle of a big discussion. The sign on one side says “Mentalism” and you can’t resist the urge to listen to these mentalists. “Who are their opponents?” – you ask yourself. Here! The sign says “Physicalism.”

At the moment the physicalists are speaking out. The speaker seems quite confident: “From a reductionist point of view, the mind is a higher level of the hierarchy, and the brain, the neuronal substrate, is a lower level. The lower level causally determines the higher; it cannot be the other way around. As Jonathan Swift explained:

And naturalists see: a flea has smaller fleas sitting on it, and they have even smaller ones that bite them, and so on ad infinitum.

Smaller fleas bite larger ones, but larger fleas never influence the behavior of smaller ones.”

“Don’t rush,” the mentalist warns, receiving the word in turn. —According to our ideologist, Roger Sperry, mental forces do not interfere with neural activity, disrupting or disturbing it, but accompany it; mental actions, with their own causal logic, occur as something additional to the actions of the brain at a lower level. The causal-effective reality of the conscious mind is a new emergent order that arises from, but is not reducible to, the organizational interaction of the neuronal substrate.”

The speaker pauses briefly; a physicalist from the opposite camp tries to intervene, but to no avail. “Sperry considers subjective mental phenomena to be the primary, causally efficient realities as they are subjectively experienced, distinct from, greater than, and irreducible to their physicochemical elements. Mental entities are superior to physiological entities, just as physiological entities are superior to molecular entities, molecular entities are superior to atomic and subatomic entities, and so on.”

The physicalist responds that all conclusions such as Sperry’s are a fraud, and that whatever any composition or configuration of neurons does is inevitably reduced to what the neurons of which it is composed do. Every so-called causal action of the mind must ultimately be traced back to some underlying neuronal component of the brain. The mind initiating changes at a lower level of the brain is like the brain substrate affecting the brain substrate without any reason. And where does the causal effectiveness of the mind, free choice, come from? “Dr. Sperry’s entire proof rests on the unprovable theorem of holism—that the whole is greater than its parts. I finished”. The speaker sits down, smiling smugly.

But the mentalists have a refutation ready. “Sperry argues that free will is that aspect of mental phenomena that is greater than their physical-chemical elements. This causally efficient mind somehow emerges from the interaction of its elements—billions of neurons. It is clear that the whole is greater than its parts. We just need to figure out how.”

The opposition does not want to give up. Someone with a big badge that says “Functionalism” comes on stage. “We functionalists view the brain-mind as a biocomputer, in which the brain is the structure, or hardware, and the mind is the function, or software. As you mentalists will no doubt agree, the computer is the most universal of all metaphors invented to describe the mind-brain. Mental states and processes are functional entities that can be embodied in different types of structures, be it the brain or a silicon computer. We can prove our point by building an artificial intelligence system that has intelligence – a Turing machine. But even here, although we use the language of software, describing mental processes as programs acting on programs, ultimately we know that it is all the action of some kind of hardware.

“But there must be higher-level mental programs that can initiate actions at the hardware level…” the mentalist tries to interrupt him, but the functionalist does not yield.

“Your so-called top-level program, any program, always runs in hardware!” Therefore, you have a causal circle: “iron” acting on “iron” without any reason. This is impossible. Your holism is nothing more than dualistic thinking in disguise.

You see that the mentalist is excited. For a mentalist, the accusation of dualism must be the ultimate insult. But someone is trying to distract you. “You’re wasting your time. The physicalists are right. Mentalism is pseudomonism; it does smack of dualism, but Sperry is also right. The mind does have causal efficacy. The solution lies in a modern, completely new form of dualism. Here is the philosopher Sir John Dual, who will explain it to you.”

When Dual starts talking, you have to admit that he knows how to make an impression. “According to the model proposed by Sir John Eccles and Sir Karl Popper, mental properties belong to a separate world, world 2, and meaning comes from an even higher world, world 3. Eccles argues that the function of mediating between the brain states of world 1 and mental states World 2 is performed by the connecting brain, located in the dominant hemisphere of the cerebral cortex. Think about it, how can one deny that the ability of creative freedom requires a leap beyond the boundaries of the system? If you are the only system available, then your behavior must be deterministic, since any assumption of the mind initiating action must inevitably lead to the paradoxical mind-brain-mind causal loop that Sperry found himself in.”

Are you completely blinded by Duala’s charisma, or is it just the accent? But what about conservation laws? And doesn’t Eccles’ link brain seem like another form of pineal gland? In your opinion, this is true. But before you can ask those questions, something else catches your attention—a Chinese Room sign attached to a closed box with two holes.

“This is a revealing device built by Professor John Searle of Berkeley University to demonstrate the failure of the functionalist idea of the mind as a Turing machine. “I’ll now explain how it works,” says the friendly man. “But maybe you’ll go into the box first?”

You are a little surprised, but agree. You don’t miss the chance to experience the Turing machine being exposed. Soon a card with text falls out of a slot in the wall of the box. There are some characters written on the card—Chinese characters, you suspect—but without knowing the Chinese language, you cannot know their meaning. There is a sign in English asking you to consult a dictionary, also in English, which gives directions for an answer card that you must select from a pile of cards lying on the table. After some effort, you find the answer card and, according to the instructions, lower it into the exit slot.

When you step outside you are greeted with smiles. “Did they understand the semantic situation at all? Do you have any idea what meaning the cards conveyed?”

“Of course not,” you say with slight impatience. “I don’t know Chinese, if that was it, and I’m not clairvoyant.”

“However, you were capable of recycling symbols, just like a Turing machine does!”

You get the point. “Thus, a Turing machine, when it processes symbols, like me, does not necessarily understand the content of the communication taking place. Just because she manipulates symbols does not mean that she understands their meaning.”

“And if a machine, processing symbols, is not able to understand them, then how can we say that it thinks?” says the man speaking on behalf of John Searle.

You admire Searle’s ingenuity. But if the functionalists’ claim is wrong, then their ideas about the relationship between the mind and the brain must be wrong. Sperry’s idea of emergence is akin to dualism. And dualism is questionable, even when offered in Popper’s new packaging. You ask yourself if there is any way to understand consciousness and free will at all. Maybe old Skinner is right – we should just analyze behavior and leave it at that?

What is all this fuss around the fountain? You wouldn’t expect to see an Indian Buddhist monk on a chariot arguing with someone who could only be a king – throne, crown and all. To your amazement, the monk begins to dismantle his chariot. First, he unharnesses the horses and asks: “Are these horses identical to the chariot, O noble king?”

The king replies: “Of course not.”

Then the monk takes off the wheels and asks: “Are these wheels identical to the chariot, O noble king?”

Receiving the same answer, the monk continues the process until he has removed everything that can be removed from the chariot. Then he points to the frame of the chariot, asking for the last time: “Is this a chariot, O noble king?”

The king answers again: “Of course not.”

You notice the irritation on the king’s face. But of course, in your opinion, the monk proved what he wanted. Where is the chariot?

You should have lunch, because the flashing exotic images make you dizzy. Then, as if by magic, Professor John C. Monist appears in front of you again and says contemptuously: “See, I told you so. There is no chariot without its parts. The parts make up the whole. Any concept of a chariot separate from its parts is a ghost in the machine.”

And now you are really confused, completely forgetting about beer and pizza. How can a Buddhist monk – a true Eastern mystic, who obviously belongs to the idealistic camp – express arguments that are grist for the mill of such a cynic as Professor Monist?

However, if you are familiar with Buddhism, there is no mystery here. The Buddhist monk (his name was Nagasena, and the king’s name was Milinda) can say those things, as can the Professor Monist, because they both deny that objects have their own nature. However, according to material monism, objects do not have a nature of their own, separate from the ultimate units of analysis – the elementary particles of which they are composed. This is radically different from Nagasena’s position of monistic idealism, according to which objects have no nature of their own separate from consciousness.

Note especially that there is no need to attribute self-nature to subjects either. (This is where Berkeley’s idealism faces criticism.) According to classical idealism, only the transcendent and unified consciousness is real. Everything else, including the subject-object division of the world, is Maya, an illusion. This is philosophically insightful, but not entirely satisfactory. The doctrine of no-self (or the illusory nature of self) does not explain how the individual experience of self arises. It does not explain our very private selves. Thus it leaves aside one of our most compelling experiences.

This is our brief overview of philosophy. Dualism faces difficulties in explaining the interaction of mind and body. Material monists deny the existence of free will and consider consciousness to be an epiphenomenon – the noise of the programs of our material biocomputer. Even idealistic monists fall short, because they too, being too caught up in the whole, question the experience of the personal self. Can quantum mechanics help unravel some of these difficult questions?

The book “The Self-Aware Universe. How consciousness creates the material world.” Amit Goswami

Contents

PREFACE

PART I. The Union of Science and Spirituality

CHAPTER 1. THE CHAPTER AND THE BRIDGE

CHAPTER 2. OLD PHYSICS AND ITS PHILOSOPHICAL HERITAGE

CHAPTER 3. QUANTUM PHYSICS AND THE DEATH OF MATERIAL REALISM

CHAPTER 4. THE PHILOSOPHY OF MONISTIC IDEALISM

PART II. IDEALISM AND THE RESOLUTION OF QUANTUM PARADOXES

CHAPTER 5. OBJECTS IN TWO PLACES AT THE SAME TIME AND EFFECTS THAT PRECEDE THEIR CAUSES

CHAPTER 6. THE NINE LIVES OF SCHRODINGER’S CAT

CHAPTER 7. I CHOOSE WITH THEREFORE, I AM

CHAPTER 8. THE EINSTEIN-PODOLSKY-ROSEN PARADOX

CHAPTER 9. RECONCILIATION OF REALISM AND IDEALISM

PART III. SELF-REFERENCE: HOW ONE BECOMES MANY

CHAPTER 10. EXPLORING THE MIND-BODY PROBLEM

CHAPTER 11. IN SEARCH OF THE QUANTUM MIND

CHAPTER 12. PARADOXES AND COMPLEX HIERARCHIES

CHAPTER 13. “I” OF CONSCIOUSNESS

CHAPTER 14. UNIFICATION OF PSYCHOLOGIES

PART IV . RETURN OF CHARM

CHAPTER 15. WAR AND PEACE

CHAPTER 16. EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL CREATIVITY

CHAPTER 17. THE AWAKENING OF BUDDHA

CHAPTER 18. IDEALISMAL THEORY OF ETHICS

CHAPTER 19. SPIRITUAL JOY

GLOBAR OF TERMS

Self-aware universe. How consciousness creates the material world. Chapter 11. In Search of the Quantum Mind

CHAPTER 11. IN SEARCH OF THE QUANTUM MIND

We saw in the previous chapter that none of the philosophical solutions to the mind-body problem can be considered completely satisfactory. Monistic idealism seems to be the most satisfactory philosophy, since it is based on the primary reality of consciousness, but even this leaves unanswered the question of how the experience of our individual, personal “I” arises.

Why is the personal self a difficult problem for idealism? Because in idealism consciousness is unified and transcendental. Then it is quite possible to ask why and how the feeling of separateness arises? The traditional answer given by idealists like Shankara is that the individual self, like the rest of the immanent world, is illusory. It forms part of what in Sanskrit is called maya – the illusion of the world. Similarly, Plato called the world a shadow theater. But no idealistic philosopher has ever explained why such an illusion exists. Some of them simply deny that explanation is possible at all: “The doctrine of Maya recognizes the reality of the multiple from a relative point of view (the world of subjects and objects) – and simply asserts that the relation of this relative reality to the Absolute (undifferentiated, unmanifest consciousness) cannot be known or described.” This is an unsatisfactory answer. We want to know whether the experience of the individual self is truly an illusion—an epiphenomenon. If this is the case, we want to know what creates this illusion.

If you saw an optical illusion, you would immediately look for an explanation, wouldn’t you? This experience of the individual self is the most permanent experience in our lives. Shouldn’t we be looking for explanations for why it occurs? Maybe if we figured out how the individual “I” comes into being, we could better understand ourselves? Can our model explain maya? In this chapter I will propose a view of the mind and brain (a system that may be called the mind-brain system) that, within the framework of monistic idealism, explains our experience of existing as a separate self.

Idealism and the quantum mind-brain

Over the past few years, it has become increasingly clear to me that the only understanding of the brain-mind that can provide a complete and consistent explanation is this: the brain-mind is an interacting system that contains both classical and quantum components. These components interact within the framework of a basic idealistic conceptual system where consciousness is primary. In this and the next two chapters I will explore the solution to the mind-body problem that this view offers. I will show that this view, unlike other solutions to the mind-body problem, explains consciousness, cause-and-effect relationships in mind-brain matters (that is, the nature of free will), and the experience of personal self-identity. In addition, we will see that creativity is a fundamental part of the human experience.

Of course, the difference between quantum and classical mechanisms here is purely functional (in the sense described in Chapter 9).

The quantum component of the mind-brain is restorative and its states are multifaceted. It serves as a means of embodying conscious choice and creativity. In contrast, because of its long recovery time, the classical component of the mind-brain can form memories and thus serve as a reference point for experience.

You may ask, is there any evidence at all that the ideas of quantum mechanics apply to the brain-mind? Apparently, there is at least indirect evidence on this matter.

David Bohm, and before him Auguste Comte, noted that the principle of uncertainty seems to operate in thinking. If we focus on the content of a thought, we lose sight of the direction in which the thought is going. If we focus on the direction of thought, then its content becomes vague. Observe your own thoughts and see for yourself.

One can generalize Bohm’s remark and argue that thinking has an archetypal component. Its appearance in the field of awareness is associated with two related variables: sign (instantaneous content similar to the position of physical objects) and association (movement of thought in awareness similar to the impulse of physical objects). Notice that awareness itself is similar to the space in which the objects of thought appear.

Thus, mental phenomena such as thought appear to exhibit complementarity. We can argue that although thought always manifests in a specific form (described by attributes such as attribute and association), between manifestations it exists as transcendental archetypes – like a quantum object with its aspects of transcendental coherent superposition (wave) and manifested particle.

In addition, there is ample evidence of a lack of continuity—quantum leaps—in mental phenomena, especially in the phenomenon of creativity. Here is a convincing statement from my favorite composer, Tchaikovsky: “Generally speaking, the germ of a future composition appears suddenly and unexpectedly… With extraordinary speed and force it takes root, sprouts, sends out branches and leaves and, finally, blossoms. There is no way I can define the creative process except through this comparison.”

This is exactly the kind of comparison a quantum physicist would use to describe a quantum leap. I won’t quote more, but great mathematicians such as Jules Henri Poincaré and Carl Friedrich Gauss similarly described their own experiences of creativity as sudden and discrete, like a quantum leap.

The same idea is very well conveyed by the comic by Sidney Harris: Einstein, with his usual absent-minded look, stands at the blackboard with chalk in hand, ready to discover a new law. The equation E = ta 2 is written on the board and then crossed out . Below it is written and also crossed out E = mb 2 . The caption reads “A moment of creativity.” Will E = mс 2 appear ? Unlikely. The comic strip is a caricature of the creative moment precisely because we all intuitively know that the creative moment does not follow such continuous, logical steps. (An excellent discussion of so-called sloppiness and lack of rigor in actual mathematics practice is given in George Paul’s delightful book How to Solve It.)

There is evidence of nonlocality in the functioning of the mind—not only the previously reported controversial data on far vision, but also data from recent experiments on brain wave coherence, which we will discuss later.

Tony Marcel’s research supports the idea of a quantum component of the mind-brain. These data are quite important and deserve special consideration.

Returning to Tony Marcel’s data

For more than a decade, Tony Marcel’s data were not fully explained satisfactorily by existing cognitive models. These data concern the measurement of final word recognition times in three-word sequences such as tree-palm-wrist and hand-palm-wrist, where the middle ambiguous word was sometimes masked by a pattern so that it could be perceived only unconsciously. It turned out that the masking effect eliminated the congruent (in the case of hand ) and incongruent (in the case of tree) influence of the first (preparatory) word on recognition time.

The absence of masking in which subjects became aware of the second word provides evidence for what is called the selective antecedent theory of word recognition. The first word influences the perceived meaning of the ambiguous second word. Only the preset (by the action of the first word) meaning of the second word is perceived. If this meaning harmonizes (disharmonizes) with the meaning of the third word being recognized, we get easier (difficulty) recognition – a shorter (longer) recognition time. If we view the mind-brain as a classical computer, as functionalists do, then in this kind of situation the computer appears to operate in a sequential, linear, and unidirectional manner, from top to bottom.

When a polysemous word is masked with a pattern, both meanings appear to be available for subsequent processing—regardless of the presence of a priming context—since similar amounts of time are required to recognize the third word in congruent and incongruent conditions. Marcel himself referred to the importance of distinguishing between conscious and unconscious perception and noted that a non-selective theory should be applied to unconscious identification (the selective theory applies only to conscious perception). In addition, it appears that such a nonselective theory must be based on parallel information processing, in which multiple pieces of information are processed simultaneously, subject to feedback. These parallel distributed information processing models are examples of a bottom-up connectionist approach to artificial intelligence devices, in which connections between different elements play a central role.

Without getting too technical, the linear and selective classical functionalist models easily explain the effect of prepriming context in cases where no masking is used, but cannot explain the significant change observed in cases of unconscious perception in experiments using masking. The same is true for theories of indiscriminate parallel processing. They can be fitted to one set of data or the other—cases of conscious perception or unconscious perception—but they cannot logically account for both sets of data in a consistent manner. Therefore, Marcel concludes in the paper cited above, “these data [for camouflage cases] are inconsistent with and qualitatively different from the data for non-camouflage cases.” Therefore, the distinction between conscious and unconscious perception has been a problem for proponents of cognitive models.

Psychologist Michael Posner has proposed a cognitive solution in which attention plays a crucial role in the distinction between conscious and unconscious perception. Attention involves selectivity. Thus, according to Posner, we choose one of two meanings when we use attention, as in the case of conscious perception of an ambiguous word in Marcel’s experiment. When we are not mindful, no choice occurs. Therefore, both meanings of an ambiguous word are perceived, as in the unconscious perception of a word disguised by a pattern in Marcel’s experiment.

So who turns attention on or off? According to Posner, this is done by a central processing unit. However, no one has ever found a central processing unit in the mind-brain, and this concept conjures up a picture of a succession of little people, or homunculi, contained within the brain.

Nobel laureate biologist Francis Crick alludes to this problem in the following story: “I recently tried without success to explain to an intelligent woman the problem of understanding how we perceive anything at all. She couldn’t understand what the problem was. Finally, in desperation, I asked her how she thought she saw the world. She replied that she probably had something like a television somewhere in her head. “So who’s watching it?” – I asked. Now she immediately saw the problem.”

We can also face it: in the brain there is no homunculus, or central processor, which turns attention on and off, which interprets all the actions of mental conglomerates, attributing meaning to them and setting up channels from a central control post. Thus, self-reference—the ability to refer to our self as the subject of our experience—is an extremely difficult problem for any type of classical functionalist model. We seek what is sought – this inherent reflexivity is as difficult to explain in materialist models of the mind-brain as the von Neumann circuit is in quantum measurement.

However, suppose that when one sees a patterned word that has two possible meanings, the mind-brain becomes a quantum coherent superposition of states—each corresponding to one of the two meanings of the word. This assumption can account for both sets of Marcel’s data—conscious and unconscious perception—without invoking the idea of a central processing unit.

The quantum mechanical interpretation of the data on conscious perception is that the context word hand projects from the ambiguous word palm (coherent superposition) a state with the value of hand (that is, the wave function collapses with the choice of only the value of hand). This state has a large overlap with the state corresponding to the final word wrist (in quantum mechanics, positive associations are expressed as large overlaps of meaning between states), and therefore recognition of this word is easier.

Similarly, in the quantum description of the incongruent case with no masking, the context word tree projects from the coherent superposition state palm to a state meaning tree; The overlap of meaning between the states corresponding to the tree and the wrist is small, and therefore recognition is difficult. When masking is used in both cases – congruent and incongruent – the word palm is perceived unconsciously, and therefore there is no projection of any specific meaning – no collapse of the coherent superposition. Thus, one can see direct evidence that the word palm leads to a state of coherent superposition containing both meanings of the word – both tree and palm (part of the hand). How else could we explain the fact that the effect of the priming (contextual) word in Marcel’s experiment almost completely disappears when the word palm is masked by a pattern?

The phenomenon of simultaneous access to both meanings of the word palm – the tree and part of the hand – is difficult to explain in the classical linear description of the brain-mind because it is an either-or description. The advantage of a quantum description based on the “both-and” principle is obvious.

I am aware that the evidence suggesting parallels between the mind and quantum phenomena—indeterminacy, complementarity, quantum leaps, nonlocality, and finally coherent superposition—is not conclusive. However, they might well point to something radical: that what we call the mind is composed of objects that are similar to the objects of submicroscopic matter, and obey rules similar to those of quantum mechanics.

Let me put this revolutionary idea in another way. Let us assume that just as ordinary matter is ultimately composed of submicroscopic quantum objects, which can be called archetypes of matter, so the mind is ultimately composed of archetypes of mental objects (very similar what Plato called “ideas”). I also assume that they are composed of the same basic substance that material archetypes are made of, and that they too are subject to quantum mechanics. Therefore, considerations regarding quantum measurement also apply to them.

Quantum functionalism

I’m not alone in this assumption. Decades ago, Jung intuited that mind and matter must ultimately be made of the same substance. In recent years, a number of scientists have made a serious attempt to explain brain research data by the existence of a quantum mechanism of the mind-brain. The following is a brief summary of their reasoning.

How does an electrical impulse travel from one neuron to another through the synaptic cleft (the point where one neuron contacts another)? According to the generally accepted theory, the signal is transmitted through a chemical change. However, the evidence for this is somewhat indirect, and E. Harris Walker called it into question, proposing a quantum mechanical process instead. Walker believes that the synaptic cleft is so small that the quantum tunneling effect may play a decisive role in the transmission of nerve signals. This effect is the ability of quantum objects to pass through an otherwise impenetrable barrier due to their wave nature. John Eccles discussed a similar mechanism, suggesting quantum effects in the brain.

Australian physicist L. Bass, and more recently American Fred Alan Wolf, noted that for intelligence to work, it is necessary that the impulse activity of one neuron be accompanied by the activity of many neurons correlated with it at macroscopic distances – up to 10 cm, which is the width of cortical tissue. According to Wolf, in order for this to happen, non-local correlations (of course, such as those suggested by the EPR experiment) are required that exist in the brain at the molecular level, in synapses. Thus, even our everyday thinking depends on the nature of quantum events.

Princeton University scientists Robert Jahn and Brenda Dunn used quantum mechanics as a model—though only metaphorical—of the paranormal abilities of the brain-mind.

Consider again the model used by functionalists—the classical computer. Richard Feynman once proved mathematically that a classical computer cannot simulate nonlocality. Therefore, functionalists are forced to deny the reality of our non-local experiences, such as ESP, since their model of the mind-brain is based on a classical computer (which is incapable of modeling or illustrating non-local phenomena). What incredible myopia! Recall again Abraham Maslow’s phrase: “If all you have is a hammer, you approach everything as if it were a nail.”

However, is it possible to simulate consciousness without non-locality? I’m talking about consciousness as we humans experience it—a consciousness capable of creativity, love, free choice, ESP, mystical experience—a consciousness that dares to create a meaningful and evolving worldview in order to understand its place in the universe.

Perhaps the brain harbors consciousness because it has a quantum system working side by side with the classical one, according to University of Alberta biologist C. Stewart and his collaborators, physicists M. Yumezawa and Y. Takahashi, and a physicist from the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. Henry Stapp. In this model, which I adapted for this book (see next section), the mind-brain is viewed as two interacting systems—quantum and classical. A classical system is a computer running programs that, for all practical purposes, obey the deterministic laws of classical physics and can therefore be modeled in algorithmic form. However, a quantum system operates on programs that are only partially algorithmic. The wave function evolves in accordance with the probabilistic laws of new physics – this is an algorithmic, continuous part. There is also a fundamentally non-algorithmizable discreteness of the collapse of the wave function. Only a quantum system exhibits quantum coherence, a nonlocal correlation between its components. In addition, the quantum system is restored, and therefore can deal with the new (since quantum objects remain forever new). The classical system is necessary for the formation of memory, for recording events of collapse and for creating a sense of continuity.

Interesting and thought-provoking ideas and data may continue to accumulate, but the point is simple: there is a growing belief among many physicists that the brain is an interactive system with a quantum mechanical macrostructure as an important addition to the assembly of neurons. Such an idea cannot yet be called generally accepted, but it is not the only exception.

The mind-brain is both a quantum system and a measuring device

Technically, we view the quantum mind-brain system as a macroquantum system consisting of many components that not only interact through local exchanges, but are also correlated in an EPR fashion. How to represent the states of this kind of system?

Imagine two pendulums hanging from a taut string. Or better yet, imagine you and your friend swinging like pendulums. Now you both form a system of conjugate pendulums. If you start to move, but your friend is motionless, then very soon he will also begin to sway – so much that very soon he will take all the energy and you will stop. Then the cycle will repeat. However, something is missing. There is a lack of unity in your actions. To fix this, you can both start swinging at the same time in the same phase. Once you start this way, you will swing together in a motion that would go on forever if there were no friction. The same would be true if you started swinging together in antiphase. These two modes of swinging are called normal modes of a double pendulum. (However, the correlation between you is entirely local; it is made possible by the stretched string that supports your pendulums.)

One can similarly represent the states of a complex system, albeit a quantum one, by its so-called normal excitation modes, its quanta, or, more generally, conglomerates of normal modes. (It’s too early to give these mental quanta names, but at a recent consciousness conference I attended we were playing around with names like psychons, mentons, etc.)

Suppose – what if these normal modes constitute the mental archetypes I mentioned earlier? Jung found that mental archetypes are universal; they are independent of race, history, culture and geographic origin. This fits quite well with the idea that Jung’s archetypes are conglomerates of universal quanta – the so-called normal modes. I will call the states of the quantum brain system consisting of these quanta pure mental states. This formal nomenclature will be useful in the following discussion.

Suppose also that most of the brain is the classical analogue of a measuring instrument that we use to magnify submicroscopic material objects to make them visible. Suppose a classical brain instrument magnifies and records quantum objects of the mind.

This resolves one of the most persistent mysteries of the mind-brain problem—the problem of the identity of mind and brain. Currently, philosophers either postulate the identity of the mind and the brain, without explaining what is identical to what, or try to define one or another type of psychophysical parallelism. For example, in classical functionalism it is impossible to truly establish the relationship between mental states and computer states.

In the quantum model, mental states are states of a quantum system, and when measured, these states become correlated with the states of the measuring device (just as in Schrödinger’s cat paradox, the state of the cat becomes correlated with the state of the radioactive atom). Therefore, in every quantum event, the brain-mind state that collapses and is experienced is a pure mental state measured (amplified and recorded) by the classical brain, from which follows a clear definition of identity and its justification.

Recognizing that much of the brain is a measuring device leads to a new and useful way of thinking about the brain and conscious events. Biologists often argue that consciousness must be an epiphenomenon of the brain because changes in the brain due to trauma or drugs alter conscious events. Yes! – says the quantum theorist – because changing the measuring device certainly changes what it can measure, and therefore changes the event.

The idea that the formal structure of quantum mechanics should be applied to the mind-brain is not new at all and has developed gradually. However, the idea of viewing the brain-mind as a quantum system/measuring device is new, and it is the implications of this hypothesis that I want to explore here.

Materialist-oriented brain researchers will object. Macroscopic objects obey classical laws, albeit approximately. How can a quantum mechanism be applied to the macrostructure of the brain so that it makes enough of a difference?

Those of us who want to explore consciousness will reject this objection. There are some exceptions to the general rule that objects in the macrocosm obey classical physics, even approximately. There are a number of systems that cannot be explained using classical physics even at the macro level. One such system, which we have already discussed, is a superconductor. Another well-known case of a quantum phenomenon at the macro level is the laser.

The laser beam travels to the moon and back while remaining pencil thin because its photons exist in coherent synchronicity. Have you ever seen people dancing without music? They move completely uncoordinated, right? But start tapping the rhythm and they will be able to dance in perfect harmony with each other. The coherence of laser beam photons arises from the rhythm of their quantum mechanical interactions, which operates even at the macro level.

Could it be that the quantum mechanism in our brain, which operates similarly to a laser, is opening up to the guiding influence of non-local consciousness, with the classical parts of the brain acting as a measuring device, amplifying and recording (at least temporarily) quantum events? I’m convinced it can.

Does the type of coherence that the laser demonstrates actually occur between different brain regions during certain mental actions? Some experimental data indicate the existence of such coherence.

Meditation researchers have studied brain waves from different parts of the brain—front and back, right and left—to find out the extent to which they are in phase. Using sophisticated techniques, these researchers showed the presence of coherence in bioelectrical brain wave activity measured in leads from different areas of the scalp of subjects in a state of meditation. Initial reports of spatial coherence in brain waves were subsequently confirmed by other researchers. Moreover, the degree of coherence was found to be directly proportional to the degree of direct awareness reported by meditators.

Spatial coherence is one of the amazing properties of quantum systems. Thus, these coherence experiments perhaps provide direct evidence that the brain acts as a measuring instrument for the normal modes of a quantum system, which we can call the quantum mind.

More recently, experiments with EEG coherence in meditating subjects have been extended to measuring brain wave coherence in two subjects simultaneously, with positive results. This is new evidence of quantum nonlocality. Two people meditate together, or become correlated through vision, and their brain waves exhibit coherence. What else, besides EPR-type correlation, can explain such data?

The most compelling evidence to date in support of the idea of quantum phenomena in the mind-brain is the direct observation of ESR correlations between two brains by Jacobo Greenberg-Silberbaum and his associates (Chapter 8). In this experiment, two subjects interact with each other for some time until they feel that a direct (nonlocal) connection has been established between them. Then the subjects maintain direct contact while in separate shielding chambers (Faraday cages) located at a distance from each other. When one subject’s brain responds to an external stimulus with an evoked potential, the other subject’s brain exhibits a “carryover potential” similar in shape and strength to the evoked potential. This can only be interpreted as an example of quantum nonlocality, due to the quantum nonlocal correlation between two brain-minds established through their nonlocal consciousness.

Don’t worry if a quantum computer seems similar to Eccles’ link brain and thus dualistic. A quantum computer is formed by quantum cooperation between some as yet unknown brain substrates. Unlike the hypothetical connection brain, it is not a localized part of the brain, and its connection to consciousness does not violate the law of conservation of energy. Before the directing influence of consciousness, the brain-mind (like any object) exists as a formless potency in the transcendental realm of consciousness. When non-local consciousness collapses the brain-mind wave function, it is through choice and recognition, not through any energetic process.

What about the fact that the quantum brain is a promising hypothesis, not an observed fact? It is true that the quantum mind-brain is only a hypothesis. However, this hypothesis is based on a strong philosophical and theoretical foundation and is supported by much suggestive experimental evidence. (The circulatory theory was formulated before the final piece of this puzzle, the capillary network, was discovered. Likewise, for mental processes to manifest and circulate in the brain, we need an EPR-correlated quantum network. It must exist.) Moreover, this hypothesis is quite specific in order to enable further theoretical predictions that can be subjected to experimental testing. In addition, because this hypothesis uses the classical (behavioral) limit as a new correspondence principle (discussed in Chapter 13), it is consistent with all the data that the previous theory explains.

All new scientific paradigms begin with hypotheses and theorizing. Philosophy turns into empty promises precisely when it does not help formulate new theories and ways of testing them experimentally, or when it does not want to deal with old experimental data that have not received an adequate explanation (as happened with material realism regarding the problem of consciousness).

The principle of complementarity between living and nonliving may be applicable here – the impossibility of studying life separately from a living organism, which Bohr pointed out. The dual mind-brain as a quantum system/measuring device is characterized by intense interaction, and it is this interaction, as we will see, that is responsible for the emergence of individual and personal self-identity. Apparently, there may also be additionality here. It may be impossible to study the brain’s quantum system in isolation without destroying the conscious experience that is its hallmark.

To summarize: I have proposed a new point of view on the mind-brain as including both a quantum system and a measuring device. Such a system includes consciousness collapsing its wave function, explains cause-and-effect relationships as the result of free choices of consciousness, and assumes creativity as a new beginning, which is what every collapse is. The following is a theoretical framework for understanding how this theory explains the subject-object division of the world and, ultimately, the personal self.

Quantum Dimension in the Brain-Mind: Collaboration of Quantum and Classical

Classical functionalism assumes that the brain is hardware and the mind is software. It would be equally unfounded to say that the brain is classical in nature and the mind is quantum. Instead, in the idealistic model proposed here, experienced mental states arise from the interaction of classical and quantum systems.

Most importantly, the causal efficacy of the quantum mind-brain system comes from a non-local consciousness that collapses the wave function of the mind and experiences the result of this collapse. In idealism, the experiencing subject is non-local and united – there is only one subject of experience. Objects move out of the realm of transcendental possibility into the realm of manifestation when the non-local unified consciousness collapses their wave functions, but we have proven that to complete the dimension, the collapse must occur in the presence of brain-mind awareness. However, in trying to explain the manifestation of the brain-mind and awareness, we find ourselves in a vicious circle of causality: without awareness there is no completion of dimension, but without completion of dimension there is no awareness.

To clearly see both this vicious circle and the way out of it, we can apply the theory of quantum measurement to the brain-mind. According to von Neumann, the state of a quantum system changes in two separate ways. The first of these is continuous change. The state propagates like a wave, becoming a coherent superposition of the states allowed by the situation. Each potential state has a certain statistical weight corresponding to the amplitude of its probability wave. A measurement introduces a second, discrete change to the state. Suddenly the state of superposition – a multifaceted state existing in potency – is reduced to only one actualizable facet. Think of the propagation of a superposition state as the development of a set of possibilities, and of measurement as a process that, through selection (according to the rules of probability), manifests only one state from the set.

Many physicists consider the selection process to be purely random. It was this view that prompted Einstein’s protesting remark that God does not play dice. But if God does not play dice, then who or what selects the outcome of a single quantum measurement? According to the idealistic interpretation, choice is made by consciousness – but a non-local unified consciousness. The intervention of nonlocal consciousness collapses the cloud of probabilities of the quantum system. There is additionality here. In the manifest world the selection process associated with collapse appears to be random, while in the transcendental realm the selection process appears to be choice. As anthropologist Gregory Bateson once noted, “Chance is the opposite of choice.”

In addition, the quantum mind-brain system must evolve over time according to the rules of measurement theory and become a coherent superposition. The classical functional systems of the brain play the role of a measuring device and also become a superposition. Thus, before collapse, the brain-mind state exists as potentialities of many possible patterns, which Heisenberg called tendencies. Collapse actualizes one of these tendencies, which, once the measurement is complete, leads to conscious experience (with awareness). The important thing is that the result of the measurement represents a discrete event in space-time.

According to the idealistic interpretation, the outcome of the collapse of any and all quantum systems is chosen by consciousness. This also applies to the quantum system we have postulated in the mind-brain. Thus, speaking about the interacting classical/quantum mind-brain system in the language of measurement theory, interpreted from the position of monistic idealism, we come to the following conclusion: our consciousness chooses the outcome of the collapse of the quantum state of our brain. Because this outcome is a conscious experience, we choose our conscious experience—but we are not aware of the process underlying that choice. It is this unconsciousness that leads to illusory separateness—identification with the separate “I” of self-reference (rather than with the “we” of the unified consciousness). The illusion of separateness occurs in two stages, but the underlying mechanism associated with it is called complex hierarchy . This mechanism is discussed in the next chapter.

The book “The Self-Aware Universe. How consciousness creates the material world.” Amit Goswami

Contents

PREFACE

PART I. The Union of Science and Spirituality

CHAPTER 1. THE CHAPTER AND THE BRIDGE

CHAPTER 2. OLD PHYSICS AND ITS PHILOSOPHICAL HERITAGE

CHAPTER 3. QUANTUM PHYSICS AND THE DEATH OF MATERIAL REALISM

CHAPTER 4. THE PHILOSOPHY OF MONISTIC IDEALISM

PART II. IDEALISM AND THE RESOLUTION OF QUANTUM PARADOXES

CHAPTER 5. OBJECTS IN TWO PLACES AT THE SAME TIME AND EFFECTS THAT PRECEDE THEIR CAUSES

CHAPTER 6. THE NINE LIVES OF SCHRODINGER’S CAT

CHAPTER 7. I CHOOSE WITH THEREFORE, I AM

CHAPTER 8. THE EINSTEIN-PODOLSKY-ROSEN PARADOX

CHAPTER 9. RECONCILIATION OF REALISM AND IDEALISM

PART III. SELF-REFERENCE: HOW ONE BECOMES MANY

CHAPTER 10. EXPLORING THE MIND-BODY PROBLEM

CHAPTER 11. IN SEARCH OF THE QUANTUM MIND

CHAPTER 12. PARADOXES AND COMPLEX HIERARCHIES

CHAPTER 13. “I” OF CONSCIOUSNESS

CHAPTER 14. UNIFICATION OF PSYCHOLOGIES

PART IV . RETURN OF CHARM

CHAPTER 15. WAR AND PEACE

CHAPTER 16. EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL CREATIVITY

CHAPTER 17. THE AWAKENING OF BUDDHA

CHAPTER 18. IDEALISMAL THEORY OF ETHICS

CHAPTER 19. SPIRITUAL JOY

GLOBAR OF TERMS

Self-aware universe. How consciousness creates the material world. Chapter 12. Paradoxes and complex hierarchies

CHAPTER 12. PARADOXES AND COMPLEX HIERARCHIES

Once, when I was talking about complex hierarchies, a listener said that this phrase caught her interest even before she knew its meaning. She said hierarchies remind her of patriarchy and power, but the term complex hierarchies has a liberating connotation. If you have the same intuition as she does, you should be prepared to explore the magical, puzzling world of paradoxes of language and paradoxes of logic. Can logic be paradoxical? Isn’t the power of logic the ability to resolve paradoxes?

As you approach the entrance to the Cave of Paradoxes, you encounter a creature of mythical proportions. You will immediately recognize him as the Sphinx. This Sphinx-like creature has a question for you, which you must answer correctly in order to gain the right to enter: what creature walks on four legs in the morning, two at noon, and three in the evening? You are momentarily confused. What kind of question is this? Perhaps your journey will be interrupted at the very beginning. You are just a newbie in this game of puzzles and paradoxes. Are you ready for what seems like a challenging riddle?

To your great relief, Sherlock Holmes comes to the aid of your Doctor Watson. “My name is Oedipus,” he introduces himself. “The Sphinx’s question is a riddle because it confuses logical types, right?”

This is true, you understand. It was helpful to learn about Boolean types before embarking on this exploration. But what now? Fortunately, Oedipus continues: “Some of the words of the phrase have lexical meaning, but others have contextual meanings of a higher logical type. It is the overlap between these two types that characterizes metaphors that confuses you.” He smiles encouragingly.

Right, right. The words “morning”, “noon” and “evening” should contextually relate to our lives – to our childhood, youth and old age. Indeed, in childhood we walk on all fours, in youth we walk on two legs, and three legs are a metaphor for two legs and a stick in old age. Fits! You approach the Sphinx and answer his question: “Man.” The door opens.

As you walk through the door, the thought comes to your mind: how did Oedipus, the mythical character from Ancient Greece, know such a modern term as logical types? But there is no time to think: a new task requires your attention. One man, pointing to another standing next to him, asks: “This man Epimenides is a Cretan who declares that all Cretans are liars. Is he telling the truth or lying? Okay, let’s see, you reason. If he is telling the truth, then all Cretans are liars, and therefore he is lying – this is a contradiction. Let’s go back to the beginning. If he is lying, then all Cretans are not liars, and he may be telling the truth – and this is also a contradiction. If you give the answer “yes”, it echoes “no”, and if you give the answer “no”, it echoes “yes”, and so on ad infinitum. How can you solve such a riddle?

“Okay, if you can’t solve a riddle, at least you can learn how to analyze it.” As if by magic, another assistant appears next to you. “I’m Gregory Bateson,” he introduces himself. “You are dealing with the famous liar paradox: Epimenides is a Cretan who says: “All Cretans are liars.” The first condition creates the context for the second condition. It qualifies him. If the second condition were ordinary, it would have no effect on its first condition, but no! It requalifies the first condition, its own context.”

Your face brightens: “Now I understand – this is a confusion of logical types.”

“Yes, but this is not an ordinary mixture. Look, the first one overrides the second one. If yes, then no, then yes, then no, ad infinitum. Norbert Wiener said that if you introduced this paradox into a computer, it would finish him off. The computer would print the sequence yes…no…yes…no…until it ran out of ink. It’s a tricky endless loop that logic can’t get out of.”

“Isn’t there any way to resolve the paradox?” – you ask sadly.

“Of course there is, because you are not a silicon computer,” says Bateson. – I’ll give you a hint. Suppose a merchant comes to your door with the following offer: “I have a beautiful fan for you for fifty bucks – that’s almost nothing. Will you pay by cash or check?” What would you do?

“I would have slammed the door on him!” You know the answer to this question. (You remember a friend whose favorite game was the question “Which would you choose?” – I will cut off your hand, or I will bite off your ear. Your relationship ended very quickly.)

“Exactly,” Bateson smiles. — The way out of the endless loop of paradox is to slam the door, jump out of the system. That gentleman over there has a good example.” Bateson points to a man sitting at a table with a sign that says, “Only two can play this game.”

The gentleman introduces himself as J. Spencer Brown. He claims he can actually show you how to get out of the game. However, to understand this, you have to look at the Liar Paradox in the form of a mathematical equation:

x = – 1/x.

If you plug in the +1 solution to the right, the equation gives – 1 ; you plug in -1, and the equation gives + 1. The solution oscillates between +1 and -1, exactly like the yes/no oscillation of the liar paradox.

Yes, you can understand it. “But what is the way out of this mad endless hesitation?”

Brown tells you that there is a well-known solution to this problem in mathematics. Let us define the quantity called i as √—1. Note that i 2 = – 1. Dividing both sides of the expression i 2 = – 1 by i gives

i= -1/i.

This is an alternative definition of i. Now let’s try to substitute the solution x = i into the left side of the equation

x = -1/x.

Now the right side gives -1/i, which by definition is equal to i – no contradiction. Thus i, which is called an imaginary number, overcomes the paradox.

“It’s amazing.” It takes your breath away. “You are a genius”.

“It takes two to play the game,” Brown winks.

Your attention is drawn to something distant: a tent with a large sign reading “Gödel, Escher, Bach.” As you approach the tent, you see a man with a cheerful face who waves at you invitingly. “My name is Dr. Geb,” he says. — I am spreading the idea of Douglas Hofstadter. I assume you have read his book “Gödel, Escher, Bach.”

“Yes,” you mutter in some embarrassment, “but I didn’t understand everything about it.”

“Look, it’s actually very simple,” says Hofstadter’s messenger condescendingly. “All you need to understand are complex hierarchies.”

“Complicated what?”

“Not anything, but hierarchy, my friend. In a simple hierarchy, the lower level provides the higher one, and the higher one does not react in any way. In simple feedback, the layer above reacts, but you can still tell which is which. In complex hierarchies, these two levels are so mixed that you cannot define different logical levels.”

“But it’s just a label.” You shrug indifferently, still hesitant to accept Hofstadter’s idea.

“You don’t want to think. You missed a very important aspect of complex hierarchical systems. After all, I have been following your progress.”

“I trust you, in your wisdom, to tell me what I’m missing,” you say dryly.

“These systems—of which the liar paradox is the most important example—are autonomous in nature. They talk about themselves. Compare them with a common phrase such as “your face is red.” A common phrase refers to something outside of itself. But the complex phrase of the liar’s paradox refers to itself. That’s how you fall into her endless deception.”

You’re reluctant to admit it, but it’s a worthwhile guess.

“In other words,” continues Hofstadter’s messenger, “we are dealing with self-referential systems. A complex hierarchy is a way of achieving self-reference.”

You give in: “Dr. Geb, this is extremely interesting. I do have a certain interest in things that relate to the self, so please tell me more.” The person who spreads Hofstadter’s ideas does not need to be asked.

“The self arises as a result of the veil – a clear obstacle to our attempt to unravel the system logically. It is this lack of continuity – in the liar’s paradox, this endless fluctuation – that prevents us from seeing through the veil.”

“I’m not sure I understand this.”

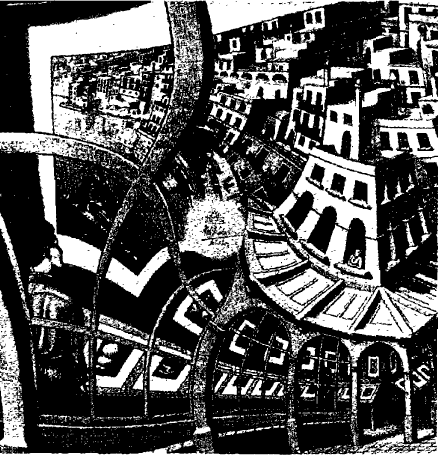

Instead of explaining again, a Hofstadter supporter persuades you to look at a painting by the Dutch artist M. C. Escher. “In the Escher Museum, in that tent over there,” he says, leading you towards it. “The painting is called “Gallery of Engravings.” It’s quite strange, but it fits exactly with the essence of our discussion.”

Img. 32.

Escher’s painting “Gallery of Prints” is a complex hierarchy. The white spot in the middle shows discontinuity

Inside the tent you study the painting (Fig. 32). It shows a young man in an art gallery looking at a painting of a ship anchored in a city harbor. But what is it? There is an art gallery in the city in which a young man looks at a ship at anchor…

My God, this is a complex hierarchy, you exclaim. Having passed through all these buildings of the city, the painting returns to the starting point where it began to begin its cyclical movement again, thus prolonging the viewer’s attention to itself.

You turn to your guide with delight.

“You get the point.” Your guide smiles widely.

“Yes thank you”.

“Did you notice the white spot in the middle of the picture?” – Dr. Geb suddenly asks. You admit that you saw it, but did not attach much importance to it.

“The blank spot containing Escher’s signature shows how clearly he understood complex hierarchies. You see, Escher could not, so to speak, fold a picture back into itself without violating the generally accepted rules of drawing, so there had to be a discontinuity in it. The white spot reminds the observer of the discontinuity inherent in all complex hierarchies.”

“From discontinuity come veil and self-reference,” you cry.

“Right. — Dr. Geb is pleased. “But there is one more thing, one other aspect, which is best seen by considering the one-step self-referential phrase “I am a liar.” This phrase says that she is lying. This is the same system as the liar paradox you encountered earlier – only it removes the nonessential form of the condition within the condition. Do you understand?

“Yes”.

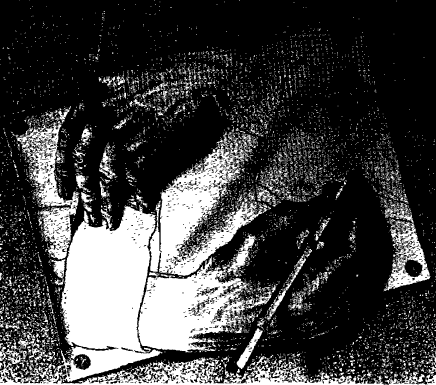

“But in this form something else begins to become clear. The self-reference of a phrase—the fact that a phrase speaks about itself—is not necessarily self-evident. For example, if you show this phrase to a child or a foreigner who is not very fluent in English, you might be asked, “Why are you a liar?” At first, he or she may not see that the phrase refers to itself. Thus, the self-reference of a phrase arises from our tacit, rather than precisely defined, knowledge of English. It’s as if the phrase is the tip of the iceberg. We call this the undisturbed level. Of course, it is unbroken from a systemic point of view. Take a look at another painting by Escher – it’s called “Drawing Hands” (Fig. 33).

Cassock. 33.

Escher’s painting “Drawing Hands”

In this painting, the left hand draws the right hand, which draws the left hand; they draw each other. This is self-creation, or autopoiesis. Moreover, it is a complex hierarchy. How does the system create itself? This illusion is created only if you remain logged in. From outside the system, where you are looking at it, you can see that the artist Escher drew both hands from an undisturbed level.

You excitedly tell Dr. Geb what you see in Escher’s painting. He nods approvingly and says with conviction: “Dr. Hofstadter is interested in complex hierarchies because he believes that the programs of our brain computer – what we call the mind – form a complex hierarchy, and from this complexity our glorious self arises.”

“But this is just a bold hypothesis, isn’t it?” You have always been suspicious of bold hypotheses. You have to be careful when scientists come up with crazy ideas.

“Well, you know, he thought about this problem a lot,” says a Hofstadter supporter wistfully. “And I’m sure that one day he will prove it by building a silicon computer with a conscious self.”